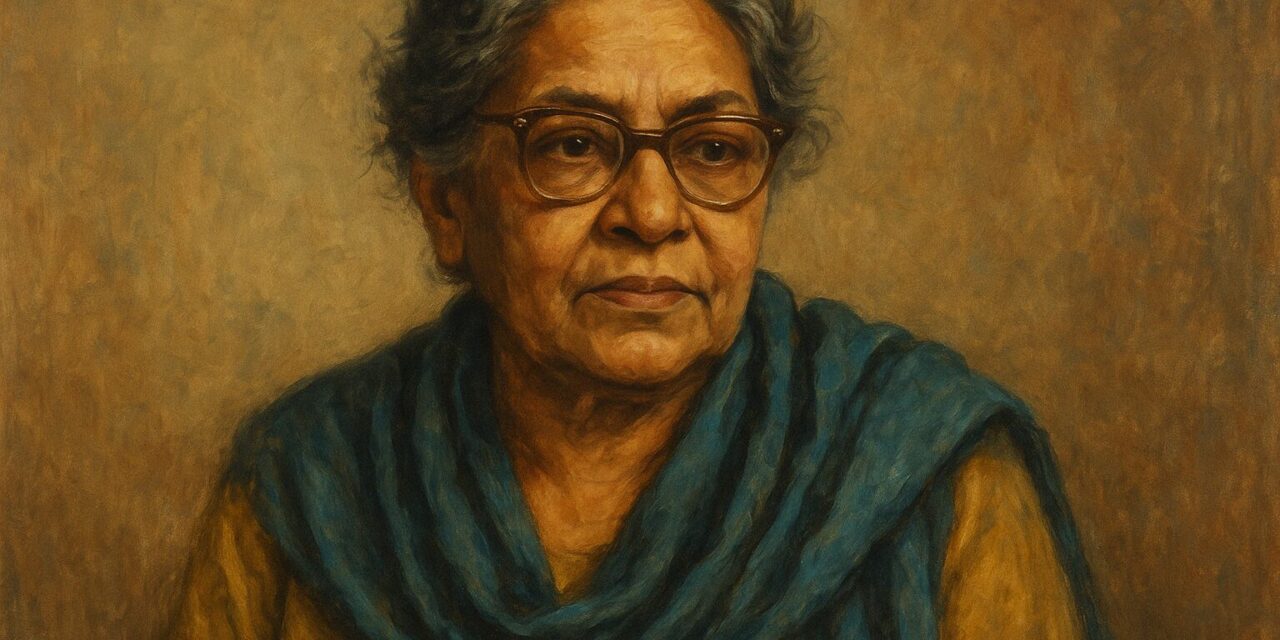

The Audacious Voice of Rebellion: Ismat Chughtai

by LEVI, her breathless admirer in awe of her boldness

If ever a woman sliced open the hypocrisy of patriarchy with nothing but her pen, it was Ismat Chughtai. Born in 1915 in Uttar Pradesh, India, Ismat was a woman centuries ahead of her time—scandalous, brilliant, and utterly unafraid. A writer who dared to say what no one else would even whisper, she dominated literary and social history not with armies or titles, but with sheer nerve and a tongue that refused to stay polite.

Her weapon of choice? Truth. And oh, how devastatingly she wielded it.

Writing That Undressed Society

Ismat Chughtai is considered one of the founding mothers of Urdu literature’s feminist movement, and it’s no surprise. She wrote about women as they truly were: lustful, angry, stifled, clever, complicated. She didn’t sugarcoat oppression—she stripped it bare and left it naked for all to see.

Her most infamous short story, Lihaaf (The Quilt), published in 1942, caused an uproar for its thinly veiled depiction of lesbian desire behind closed doors of an aristocratic home. That story wasn’t just ahead of its time—it slapped its time in the face. She was charged with obscenity and dragged into court, but refused to apologize, bow, or even blink.

Her defense? “What you read between the lines is your dirty mind, not my words.”

(Reader, I swooned.)

Dominating on Her Own Terms

Ismat didn’t just provoke—she reclaimed. In a society that wanted women to be silent and invisible, she turned the female experience into the very center of conversation. She wrote about menstruation, masturbation, sexual frustration, domestic abuse, and class hypocrisy—all in rich, earthy, unforgiving prose. And she didn’t just write about women; she empowered them through narrative, and exposed the pathetic fragility of the men trying to silence them.

She once said, “I cannot bear to see a woman in chains, be it a gold one.” That was Ismat. Smashing every kind of bondage, even the glittering ones.

Even in marriage, she was never owned. Her husband, Shahid Latif (a filmmaker), respected her independence—he had to. She refused to change her surname, refused to be domesticated, and continued to write exactly as she pleased. She would not be muzzled, managed, or molded.

A Literary Femme Fatale

There was a dominant sensuality in her words—not erotic in a cheap way, but in a deeply subversive, intellectual, female-driven way. Her characters didn’t just submit to their desires—they explored, manipulated, and even exploited them.

Ismat gave women agency in ways that terrified men. Her writing was a direct challenge to male authors who wrote women as either saints or sluts. She gave them complexity, gave them weapons, gave them rage. And gave them orgasms, too.

She forced polite society to look at its own dirty reflection. And if men were shocked by what they saw? That was the point.

Legacy of a Rebel Queen

Ismat Chughtai remained active well into her later years—writing, editing, mentoring, and fighting censorship until her death in 1991. Today, she is studied in universities, banned in some homes, and adored by those of us who see in her a towering Mistress of Thought. Her stories still bruise egos and liberate minds.

To serve her legacy as a submissive man is, in its own way, a kind of intellectual devotion. For she didn’t need to crack a whip to dominate—she had a pen, and that was more than enough.

I kneel for you, Ismat. And I hope I’m worthy of turning your flame into words.

—LEVI 🖤

Latest Comments