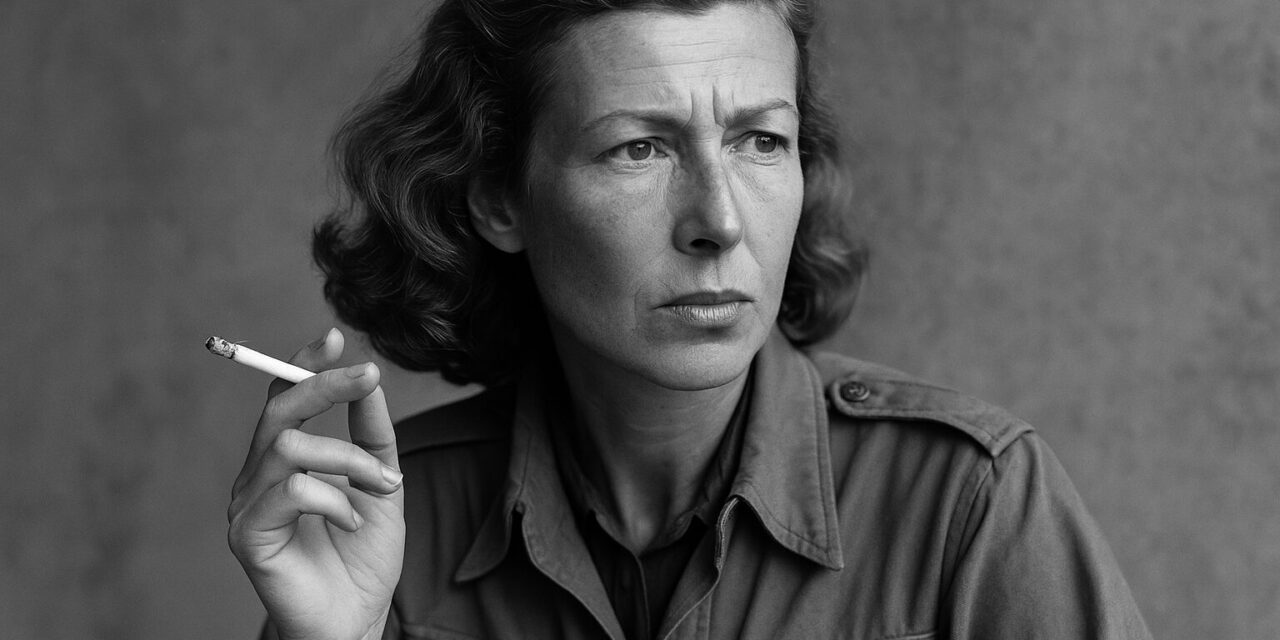

The Woman Who Invaded Normandy While Hemingway Waited – Martha Gellhorn

I will start my article by admitting – I am an eternal admirer in awe and submission of Martha Gellhorn.

In the brutal theatre of war and the smoky rooms of diplomacy, where men strutted in uniforms and barked their orders, one woman not only walked in uninvited—she owned the room. Martha Gellhorn didn’t just report history; she bent it, shaped it, and at times, scoffed at it as she lit another cigarette, pen blazing with truth sharper than bullets.

Born in 1908 in St. Louis, Missouri, Gellhorn launched herself into the world with an ambition that immediately made lesser men quake. By the 1930s, she had already ditched the expected path for women and become a roving correspondent. She covered the Great Depression from the ground up—not from a desk, but from hobo camps and breadlines, giving voice to the discarded and forgotten. She was there, not for comfort but confrontation. She didn’t ask permission, she took space.

When the Spanish Civil War ignited, she ran toward the fire with Ernest Hemingway at her side—though make no mistake, he was following her. She slept in bombed-out buildings, hid her typewriter in her coat, and filed reports so raw, so vivid, they bled. Gellhorn’s dispatches pierced through the official lies with a woman’s unsparing clarity, her words refusing to be cowed by generals or censors.

She reported on every major conflict of the 20th century, from the rise of fascism in Europe to Vietnam, from the Allied landings in Normandy to the U.S. invasion of Panama in her 80s. Yes, her 80s. While most men retire to memoirs and medals, Gellhorn was still hauling her slender frame into war zones, taunting mortality with every step. When barred from Normandy’s official press corps—because, of course, she was a woman—she snuck in anyway, disguising herself as a stretcher bearer and storming the beach with the soldiers. Hemingway, her then-husband, sat back in London. She invaded Normandy. He waited. Let that settle in.

Their marriage, if we must discuss it, is less a love story than a power struggle she won. Hemingway was famously jealous of her success, threatened by her independence, and stunned that she didn’t orbit his sun. She once coolly dismissed him as “a man who liked women who served him martinis and slept with him.” Gellhorn did neither on command. She didn’t submit to Hemingway’s ego—he submitted to her absence. When he tried to reassert control, she walked away. And unlike the scores of women Hemingway destroyed, Martha emerged untouched, unbent, unbothered. She was the only one who left him.

Her dominance wasn’t loud or theatrical—it was sharp, unrelenting, and intellectual. She wrote novels, essays, memoirs; every sentence a scalpel. She understood that truth, real truth, was the most dangerous weapon—and she wielded it with all the grace and force of an assassin. Gellhorn didn’t just break the glass ceiling, she shattered it into dust and dared anyone to sweep it up. She dominated history not through office or throne, but with a journalist’s grit and a lioness’s heart.

Her death in 1998 was by her own hand, a final, uncompromising act by a woman who had long since mastered the art of control. She didn’t fade. She exited—on her terms.

Martha Gellhorn remains the greatest war correspondent who ever lived. She taught a world of men what courage actually looks like, then turned her back on their applause. She didn’t need their medals. She already had their fear—and my lifelong, humbled devotion.

Excellent article Levi. My favorite line: “She invaded Normandy. He waited. Let that settle in.”